1. Introduction

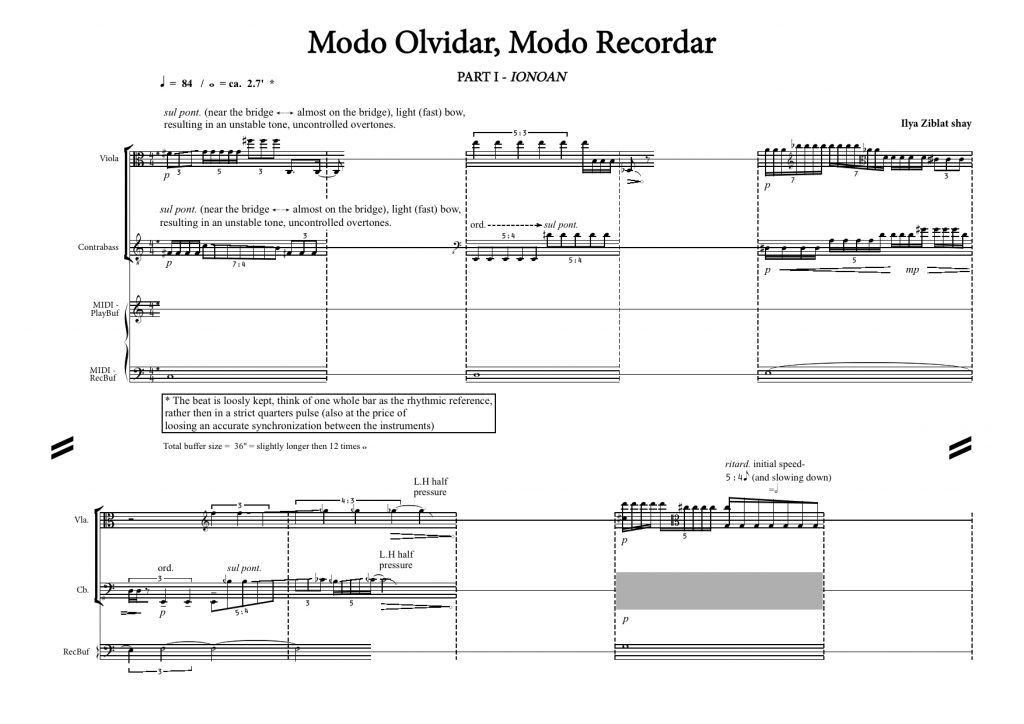

Modo Recordar, Modo Olvidar (MRMO) is a composition for viola, contrabass, and electronics (played by a third musician). I will use it as a case study to examine the relationship between improvisation and structure, or musical form. I wanted the composition to have a definite shape, with clear transformations of sound and group dynamics, musical “turns,” and changes of direction. At the same time, I wanted it to have a flexible structure, allowing passages to be stretched or compressed. This chapter will focus on how MRMO allows for this kind of flexible structure and the effect it has on the performance.

In Part 2, I will discuss a recording of MRMO by Hatzatz. This recording reveals fundamental “inaccuracies”: differences between the score and what the musicians actually play. I will suggest that this relatively high degree of interpretative freedom is a result of my compositional approach. In Part 3, I will focus on the composition itself, describing how my prescribed ideas are developed through improvisation. I will describe the relationship between the notated and improvised parts, using the concept of style, or idiom, to show how the musicians assimilate the notated parts and elaborate on them through improvisation. The notation I use – boxes along a flexible timeline – is designed to make improvisation the basis of the musical form. Finally, I will describe the role of the electronics in linking improvisation and structure: the computer records the musicians as they play, processes the recorded samples, and plays them back to the musicians. The overall result is a combination of sampled and live sounds: an unfolding sequence of previous and current improvisations.

MRMO offers another perspective on freedom and fixity. The approach here differs from that of my other compositions. MRMO has a predefined shape that is, however, constructed from improvised building blocks. Improvisation, once comprehended as compatible with, rather than opposed to, structure, can serve as a model for a paradigm of freedom which does not oppose fixity but is complementary to it. MRMO is also the earliest composition of the four discussed in this thesis, and I will use it to introduce some of the ideas which will be developed in the other chapters: for example, flexibility or the relation between notation and improvisation.

2. MRMO Played by Hatzatz

This version of MRMO was recorded by Hatzatz in 2012 during a live concert. Comparing this particular recording with the score reveals many instances where the musicians play something different from what is notated. For example, at the very beginning the viola and bass “ignore” the notes in the score.

This kind of interpretation was possible because Hatzatz had performed MRMO regularly by the time of the recording. However, it was not only the ensemble’s familiarity with the piece that had made a precise realization of the score seem unnecessary but also our experience – both as individual musicians and as a group – with other musical situations involving both improvisation and composed content. This meant that, instead of sticking to the notes and rhythms as they were written, the ensemble attempted to re-create the intention behind them even if that involved playing notes and rhythms that were not notated. We felt that, compared with earlier performances which had followed the score more closely, this “radically” free realization of MRMO was more engaging and produced a better flow of musical ideas and responses both within the group and between the musicians and the score. In that sense, my initial ideas entered into a network of effects and influences that allowed the performance to become much more absorbing than a more “faithful” interpretation of the score would have been – both in the sense of realizing the structure and of allowing the notated material to evolve through improvisation.

This raises the question of whether the score of MRMO could enable another group of musicians to perform the piece without my participation as a performer. In what follows, I will describe the structure of the composition, how improvisation is presented in the score as a musical resource in order to create structure, and the decisions I made about the notation in order to communicate my ideas to potential performers.

3. Musical Form and Improvisation

The most important aspect of MRMO is its musical form. I conceived a framework around which my ideas could be interwoven with those of the performers. To begin, I will take a closer look at the idea of musical form. The Harvard Concise Dictionary of Music provides two definitions:

(1) In the most fundamental sense, the shape of a musical composition is defined by all of its pitches and rhythms. In this sense, there can be no distinction between musical form and musical content, since to change even a single pitch or rhythm that might be regarded as part of the content of a composition necessarily also changes the shape of the composition even if only in detail. (2) From this follows the application of the term form to abstractions or generalizations that can be drawn from groups of compositions for purposes of comparing them with one another . . . [e.g.] Binary and ternary form; Rondo; Variation; [etc.]. (Randel, 1978)

The two definitions describe music in which the material is composed prior to the performance, or, in other words, fixed. I wanted to introduce an alternative to that idea, one that would be based on improvisation and in which the improvisation would be indispensable, that is, playing a functional role rather than just adding an extra layer of embellishment on top of an otherwise fixed framework. However, I did not want to dispense with the fixed framework entirely.

Once the musical material is not fixed, other structural building blocks that allow musical decisions to take place in real time have to be provided. In other words, the work must be structured so that it allows for specific characteristics to be retained in each and every performance. To a certain extent, my vision of MRMO agrees with the notion of form as an abstraction or generalization (the second definition, above), in the sense that the composition can generate various realizations that are substantially different from one another – involving different pitches and rhythms – yet can be seen to have the same origin, as they have similar structural characteristics. How could a composition that would allow improvisation to have such an essential role look?

As in my other works, the main consideration was that the score would set the relationship between the free and fixed components so that the improvisation and the pre-composed ideas would form an unbroken continuum. A performance of such a composition should make it impossible for listeners or performers to separate the process of realizing the score from improvisation.

MRMO consists of several sections that are played continuously without pause, forming a musical development. According to the Harvard Concise Dictionary of Music, “development” is defined as

the working out of previously stated thematic material, usually by means of application of techniques such as sequence and imitation . . . in such a way as to produce a series of modulations and a sense of increased structural tension. (Randel, 1978)

Once more, this definition relates to a different musical context from MRMO: a traditionally notated composition in which the development is worked out by the composer in advance. But the idea of an evolving musical process which grows from a beginning statement and unfolds gradually fitted well with my intentions. It could be also carried out “spontaneously” – as an improvisation in real time.

3.1 Musical Form and Improvisation in MRMO

The process of musical development in MRMO can be described as follows. In the first section (page 1) the viola and bass play a succession of bar-long phrases and silences. The repeating alteration of instrumental action and silence creates a characteristic momentum. It forms an opening statement that provides a thematic identity for the following development, and sets the performers’ “behavior” for the next two sections. At this point, the music is still precisely notated, not allowing any improvisation whatsoever.

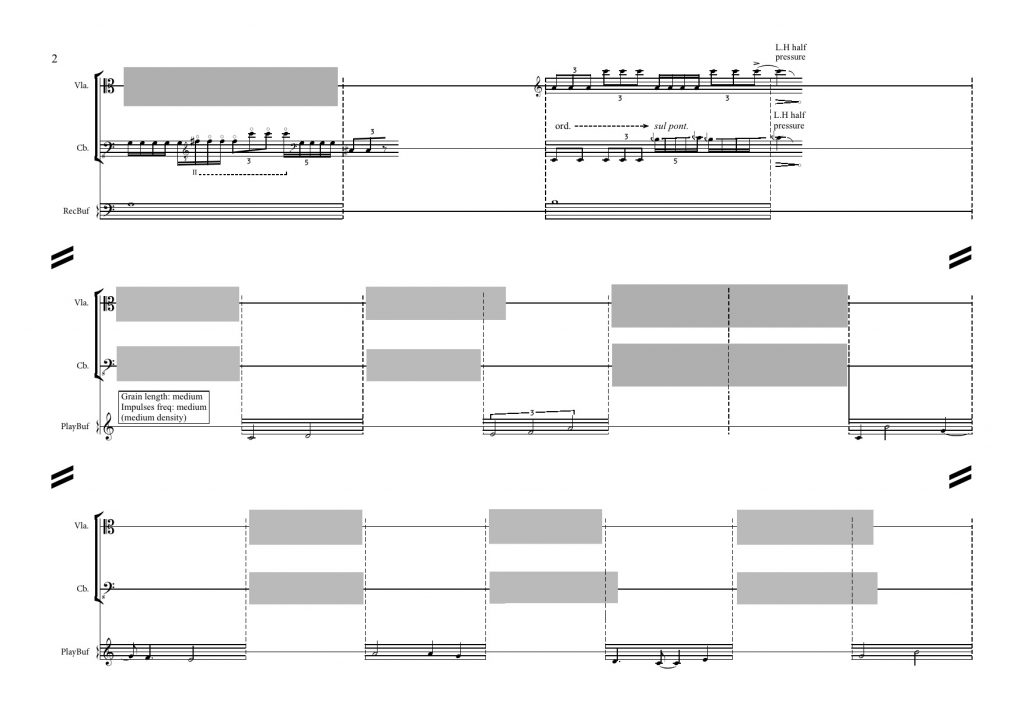

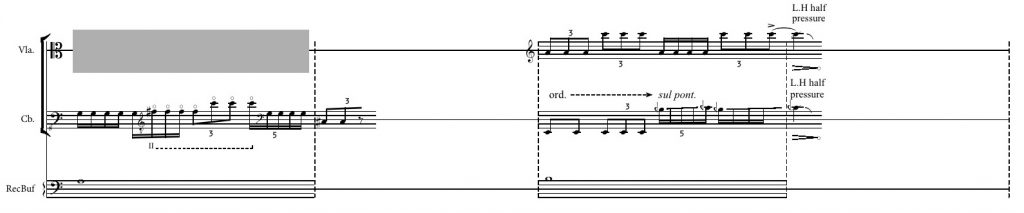

Next, the score starts to introduce improvisation (marked by gray boxes, page 2). The freedom of the musicians in this part is relatively restricted, since the improvisational instances are fixed within the timeframe of the bar lines. Instruments and electronics engage in an antiphonal call-and-response, which will stand as a point of departure for the following section.

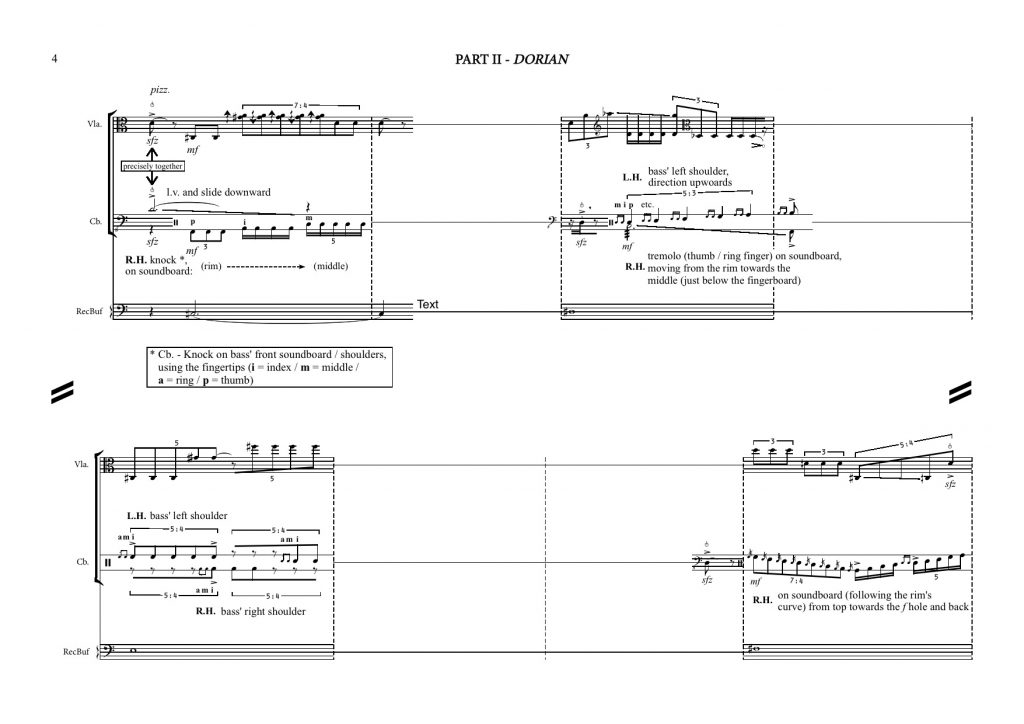

In the third and last section (page 3), the electronics and acoustic instruments gradually intermix, and the role of the instruments decreases as the electronics become more and more prominent. Here, also a more elaborate freedom becomes possible. The starting point is the antiphonal alternation between acoustic and electronic sounds. However, at this point, precise timekeeping is no longer necessary: the previously stated thematic content and the distinctive timekeeping (alternating playing and silence) have already been embedded into the players’ “instincts,” and so the improvisation can become a natural continuation of the prescribed notes. As in the recorded version by Hatzatz, the musicians can freely use the information in the score in order to play new notes. The end of this section also ends the first part of the composition, reaching a brief climax (the takeover by the electronics) which is immediately cut by a new part: a new instrumental beginning, introducing more notated statements which will now function as the starting point for the following, similarly shaped development (page 4).

Each of the sections represents a different function in the overall structure of the composition. The first is a thematic exposition which establishes the tone for what will follow – setting a defined musical environment containing certain instrumental gestures, a characteristic musical momentum, and, as a result, a distinct sonority. The second section sets in motion the expansion of the exposition by introducing improvisation into the score. The third section takes the improvisation further by allowing the musicians to dwell freely within a “familiar” environment. The playing becomes increasingly open as the performers pass from one section to the next, and freedom is assigned to wider and wider levels of the composition, starting with the interpretation of notated phrases and gradually becoming the key factor that forms the overall musical shape, as the gray boxes become the dominant part of the notation

3.1.1 Circles

In order to put my ideas into a broader context, it would be useful to compare them with the works of other composers. Another piece which connects structural development and improvisation is Circles (1961) for voice and instrumental ensemble by Luciano Berio. This work also introduces freedom into the performance gradually, starting with notated gestures and using boxes to signify freedom.

The performer “learns” the musical idiom – the identity of the composition formed by the notated sections – and later makes use of this knowledge in the improvisation. This is an important process, since it enables the transition from playing the prescribed score to improvising.

Although Circles uses a similar notation to MRMO, the freedom in Circles is fundamentally different. Berio was interested in leaving undefined only those aspects of the score which could stay so without “harming” the overall pre-composed identity of the piece. While Berio makes use of open notation as a single element embedded within an otherwise fixed environment, I tried to use it as the building blocks for the entire structure. In this way, improvisation in MRMO takes place not at the fringes of the musical activity, but at its very center; at the same time, there is no clash between musical freedom and the already existing structural framework. In the following, I will deal with my approach to the score: “box notation.”

3.2 Box Notation

While working on MRMO I tried to come up with a notation system that could convey both the real-time freedom of the musicians as well as concrete structural features. After experimenting with several possibilities that did not satisfy me in the sense that they could not provide an adequate mix between freedom and fixed properties, I decided on “box notation.”

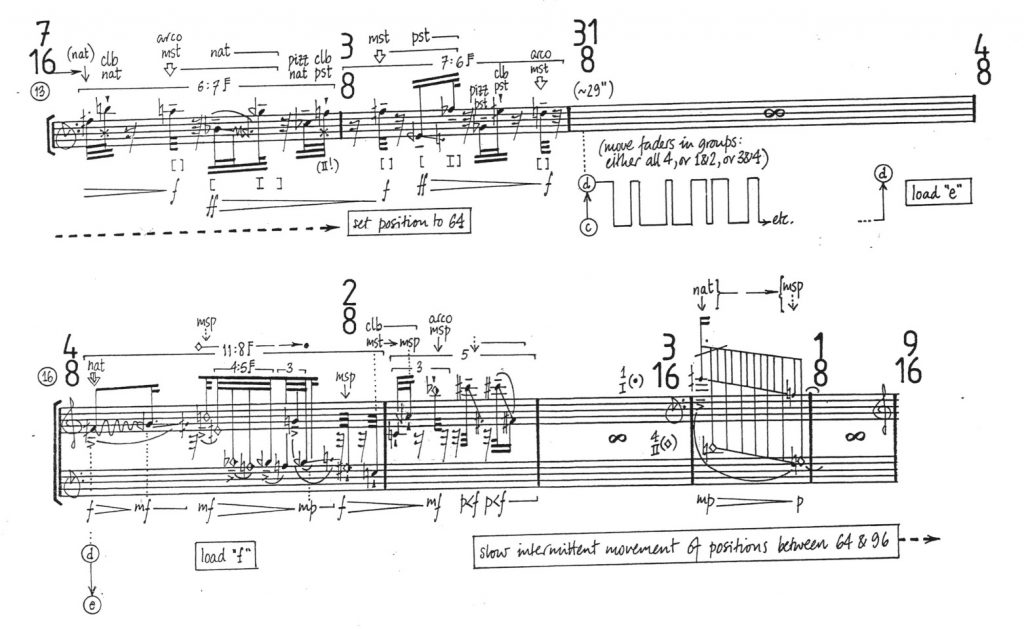

(click to enlarge each image separately)

Passages to be improvised are marked by gray boxes. As the gray boxes are “empty” the players are encouraged to “fill” them as they wish, that is, by improvising. The gray boxes can also be stretched or compressed, thus allowing for a flexible timeline, admitting various solutions to different musical settings: a more precise position in relation to the bar lines and traditional rhythmic notation or a freer approach with less exact timing of musical events and a looser relationship between the instruments (for example, MRMO, Part III). Two earlier experiments in notation, and the eventual box notation method.

By combining these qualities, box notation allows the musicians to weave predetermined features and improvisation into a single musical narrative.

3.3 Notation and Improvisation: Idiomatic Consistency, Evolving Freedom

The gray boxes mark a timeframe for the musicians to play but leave out the rest of the information (rhythm, pitch, and so on). However, instead of leaving the content of the improvisation entirely free, I chose to “interfere” by instructing the performers to base their improvisation on the notated material. These instructions, which contain rhythm and pitch material, playing techniques, and other musical expressions, set the tone for the improvisation to follow.

The relation between the prescribed material and the improvisations could be explained in terms of “idiomatic consistency”: an established musical style which sets a local idiom for the composition. In that sense, I agree with Earle Brown, who states that it is the composer’s responsibility to “create conditions which . . . won’t be violated stylistically” (Brown in Bailey, 1993, p. 63). It is the task of the composer to define clear syntactical “rules,” as much as to avoid providing the performers with exact “words,” thus creating the necessary conditions that allow improvisation to be derived from a certain musical idiom.

My notion of idiomatic consistency also agrees with Derek Bailey’s (1993) observation that the particular musical settings created by such genres as jazz, flamenco, or traditional Indian music are the creative engines behind the improvisations. However, Bailey uses this idea to designate a unique status for free improvisation, “non-idiomatic,” thus creating a dichotomy which is less relevant here. My notions of freedom and fixity can be applied to any piece of music, improvised or composed. The more general division between idiomatic and free improvisation is, in my opinion, inadequate to establish a constructive perspective that could be used to understand or create music.

Another perspective from which we could observe the “agreement” between idiomatic consistency and freedom is by looking at the work of, for example,Sun Ra, The Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM) and the Art Ensemble of Chicago, or Archie Shepp. The African or African-American traditions and roots which stand at the very base of this music aspire to improvisational freedom, rather than functioning as a departure point from which this music is trying to break away. In the work of these musicians there seems to be no dispute whatsoever between freedom and tradition or style. The improvisations stem directly from historical, folkloristic, and social circumstances, and continues the aesthetic conventions of free jazz or free improvisation. In MRMO I create such conditions through the notation, but I also let the music evolve freely, trusting that my input can become the root of an elaborately improvised performance.

3.3.1 Blattwerk

Another example of a composition that combines notation and improvisation is Blattwerk for cello and electronics by Richard Barrett (2002a). Barrett chooses to notate the improvisatory passages with the mathematical symbol for infinity (∞): “The ‘silent’ bars marked with ∞ (in the place of a rest symbol) are lacunae in which improvisation may take place” (Barrett, 2002a, n.p.).

Barrett discusses the inessentiality of stylistic (idiomatic) consistency:

The high degree of discontinuity of the notated music is intended to create structural/expressive “questions” which can only be answered (if at all) by improvisatory actions. On the other hand no kind of musical material should be excluded a priori on grounds of consistency or taste. One could imagine a context for anything. . . . In any case, on a first hearing it will not always be possible to tell the difference between the notated and non-notated music; and there is really no reason why it should always be. (Barrett, 2002b, n.p., italics in original)

The lacunae bars are empty “placeholders” – signs that indicate improvisation. The improvisations in Blattwerk may, potentially, evolve in directions which have very little to do with the musical idiom in the rest of the piece. Yet this does not mean that Barrett’s approach ignores the relation between the improvised and notated materials. Rather, it perceives improvisation as an answer to open questions. The improvisations are a way to respond to the notated material, reflecting on the the pre-composed ideas. In comparison, in MRMO, I chose to explicitly direct the attention of the improvisers to the notated material. This seemed to me a more straightforward solution, which better serves my objective of creating the structure of the composition from the improvisation, which requires a certain degree of control over the content.

But even though my approach involves a direct intervention in the improvisation, my aim was not to restrict the freedom of the musicians. Instead of providing a context which is entirely open, I chose to focus the creative energy of the improvisers through a more precise filter. The result should not be judged for its restraining effect, but, rather, for its creative quality: the players, after internalizing the notated parts, can produce new sounds and gestures which stem from the prescribed information as an improvisatory language. By specifying a “local” idiom for each part of the composition, these fine-tuned improvisations establish the structure of the composition.

3.4 Flexible Timeline

According to the Oxford Dictionary of English, a timeline is “a graphical representation of a period of time, on which important events are marked” (Stevenson and Lindberg, 2011). So, for a composer, a timeline can be used to communicate the order of musical events and the temporal relations between them.

The score of MRMO indeed presents all the events in the order in which they will take place during a performance. However, MRMO’s timeline can also be described as flexible, as it extends the traditional notion of a timeline and connects it with the notion of freedom. There are two aspects to this flexibility: the vertical and the horizontal. Vertical flexibility describes the misalignment between the different staves of the musical system, which are “floating” in relation to each other. I chose to use dashed bar lines to indicate that events which are lined up vertically do not necessarily have to happen simultaneously. The score indicates: “The synchronization between the instruments should be only loosely kept: although notated in the score as such, the result should sound out of phase.” Vertical flexibility points towards an enhanced freedom of interpretation, starting from the composed material and lasting the entire score. Horizontal flexibility describes the relationship between the timeline and real time: the order of musical events is set by the score, but their durations can vary. The score provides a continuous graphic representation of time but does not specify how long anything should last. This allowed me to include various notation methods within the same score – prescribed notes and rhythms, text instructions, gray boxes, and the use or absence or bar lines – presenting different proportions of composed material and improvisation.

The flexibility of the timeline establishes a strong connection between performer and score based on the existing relationship between the visual representation and performative aspects of time and sound. The following comment by Morton Feldman originally referred to Earle Brown’s idea of time-notation, but it also describes accurately the effect of a flexible timeline:

The sound is placed in its approximate visual relationship to that which surrounds it. Time is not indicated mechanistically, as with rhythm. It is articulated for the performer but not interpreted. (Feldman in Bailey, 1993, p. 60)

Time is suggested as a musical component with elastic qualities, shaped both by the composer and the performers. My notion of a flexible timeline enables a clear description of musical structure, while allowing space for improvisation.

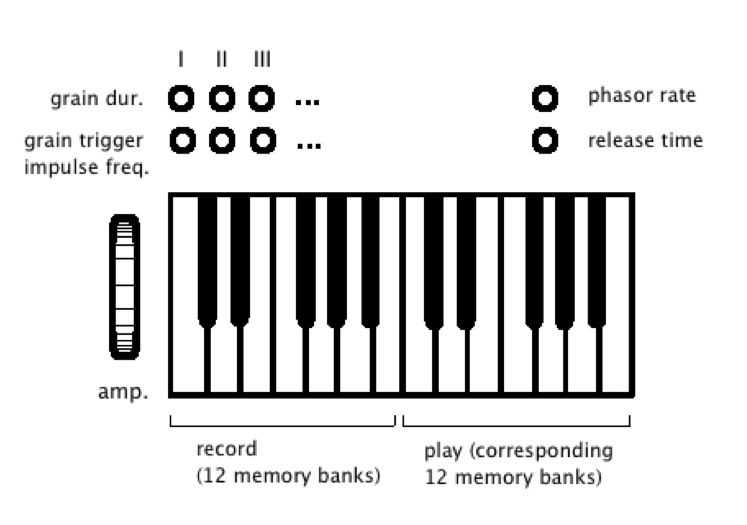

3.5 The Electronic System in MRMO: Sampling, Structure, and Improvisation

Electronics play an essential role in MRMO. The computer system samples the instruments in real time and plays back a processed version of the recorded material. Certain parts of what the musicians are playing are recorded and saved as digital buffers (the computer’s “memory banks”). These contain distinct sounds from different parts of the piece (different “idiomatic” improvisations). They are then played back to the musicians, who react to them in real time. The buffers are being repeatedly recorded, newer content written over older content, so the overall electronic soundscape goes through a continuous transformation.

Steve Lake, producer of the Evan Parker Electro-Acoustic Ensemble’s ECM releases, discussed the relation between sampling and improvisation:

The musicians play, and their sounds are sampled by the treatment stations and fed back to them (think of encountering a duplicate of yourself from a parallel universe, almost you but not you). There are many more unknowables than in ‘normal’ improvising. The players have to see the whole soundscape unfolding and contribute to it tellingly while having no idea of what may happen to the notes and phrases they are generating. Those phrases might be returned to them immediately, back-to-front or upside down, or come back to haunt them half an hour later. (Lake, 2004, n.p.)

The impact of the improvised notes is thus extended beyond the moment in which they are first played. “Echoes” of former improvisations mix with the current one, creating a developing matrix of old and new musical ideas – which is, in fact, the gradual unfolding of a musical structure. As understood by Lake, this process not only forms the listeners’ experience but also affects the improvisers who have to interact with their own ideas.

The notion of sampling within a notated/improvised setting is central to this case study. The inherent ephemerality of the improvisation is overridden, “crystallizing” the improvised sounds and allowing them to mix with the composed elements, notated or recorded. The score of MRMO also uses gray boxes for the computer part. Like the gray boxes in the staves for the viola and contrabass, these represent the material which will be sampled. The notation thus combines the samples and live sounds into one compositional structure.

4. Conclusion

In MRMO, I tried to develop a framework that clearly defines musical information – the notated material, the relationship between the instruments and the computer, the structure – as much as it relies on improvisation. The detailed notation, the linear timeline, the relatively straightforward functionality of the electronics (compared with the interactive computer system in The Instrument), all demand from the musicians a precision in their realization. At the same time, most of the information is “missing,” in the sense that notes and rhythms have to be invented in real time.

It is the structure of the composition – the overall musical shape which unfolds during the performance – that provides the center around which both prescribed information and improvisation exist. Making use of the potential of my notation system (the emptiness of the gray boxes, their graphic elasticity, and their relationship to the instructions), I designed the structure so it can demonstrate clear and recognizable features – a musically ”logical” development, sharp changes of sounds, and so on – yet at the same time remain flexible. The main conclusion to be drawn from this case study is that musical form should avoid being too amorphic as much as being too rigid. Many works, composed or improvised, tend towards one of these poles, making the experience of listening or playing tiring. A balance between the two is, in my opinion, essential to the creation of an engaging musical result.

The score of MRMO opens a creative space that is shared by the performers and the composer. The notation defines certain interrelations between the players themselves, and between them and the composed ideas. In this sense, the score can be perceived as an opening for a collective musical act. It is a framework within which musical interactions can take place rather than a rigid and restrictive set of prescribed instructions.

MRMO demonstrates the ability of a composition to admit improvisation without losing any of its potential merits. Being the earliest of the four pieces discussed in this thesis, MRMO was an important phase in developing compositional tools that could be reused in other works and hopefully also by other composers and improvisers.